The Gay Bar versus the Academy

Despite recently receiving my masters in Visual and Critical Studies I have always had a love/hate relationship with critical theory. Within my graduate program there is a running joke that critical theory is “like a stain you can’t get out.” My biggest frustration is the disconnect I feel between what is discussed and generated within the sterile walls of the academy and the communities that exist beyond those walls who are often the subjects of the theories produced and studied. Over the past two years, as I was buried in theory and thesis writing, I found myself often questioning the relevance of philosophical texts for those who exist within activist circles, public services, and that which is often described as “on the ground.”

My frustration with the inaccessibility of critical theory hit home after reading a portion of the text, Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of Sex by philosopher, Judith Butler in a course entitled Critical Race Art History. Butler is infamous for her incredibly dense and often incomprehensible language that consists of the kind of sentences that most people have to read over and over to gain even the slightest understanding. In Bodies that Matter Butler discusses the materiality of the body and the repetitive performativity of gender, pushing for the destabilization of normative gender binaries—or at least, this is what I’ve gathered from my second and third reading. This theory speaks directly to our intimate understandings of bodies, desire, and expressions of gender. It is immensely relevant for many people and therefore can be considered a potentially liberating text and yet is written in a language that is inaccessible to so many people beyond and even within the academic institution. This is the contradiction of critical theory that drives me a little bit mad. When expressing this discontent in class, my professor, art historian Jacqueline Francis, gently intervened asking where it is that one has the experiences that inspired Butler’s text: the gay bar or the academy?

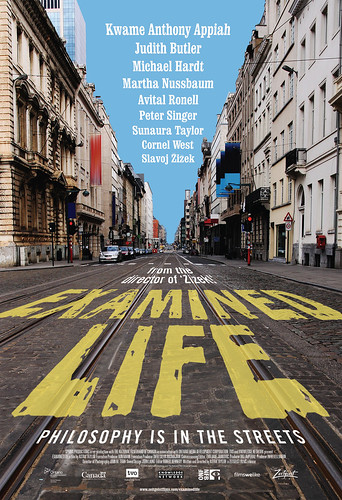

I was reminded of this question after watching Examined Life at the Red Vic Movie House last month. Examined Life, produced by Zeitgeist Films and Sphinx Productions and directed by Astra Taylor, features eight philosophers who are interviewed by Taylor in public, mostly urban, spaces including Central Park and Times Square in New York City, the Mission District in San Francisco, an airport and a dump. The philosophers include Kwame Anthony Appiah, Judith Butler with Sunaura Taylor, Michael Hardt, Martha Nussbaum, Avital Ronell, Peter Singer, Cornel West and Slavok Zizek. The subtitle of the film “Philosophy is in the Streets,” sounds like a slogan for an action movie and yet, I admit that it is a fitting description. In Examined Life the often impenetrable written language of theory and philosophy takes the form of a conversation complete with all the nuances of cadence, accents, hand gestures, body language, and facial expressions. With the backdrop of cityscapes, the philosophy becomes a kind of performance. Appiah discusses globalization as an opportunity to appreciate and understand site-specificity and cultural relativity while walking through and resting in an international airport. Singer makes a case for our responsibility to use our resources ethically among the advertisements, busy storefronts, and neon lights of Times Square. Zizek discusses human impact on ecology as he sports an orange construction vest and paces among trash heaps at a dump. Butler considers the possibilities of the body with Sunaura Taylor as they walk through San Francisco’s Mission District. Weaving these locations and thoughts together are soundbites from West, whose own interview took place in the backseat of a taxi cab as Taylor drove him throughout Manhattan.

Cornel West being interviewed by Astra Taylor in the backseat of a cab in New York City for the film Examined Life

There was a humbleness to seeing philosopher rock-stars like Butler and Singer strolling around the streets of cities, making bad jokes, and stumbling over their words or observing Hardt as he theorizes about revolution while struggling to dislodge his row-boat from rocks in the lake of Central Park. These scenes are a reminder, if even only metaphorically, that philosophy and theory emerge from the everyday. Certain moments of this film made this connection all the more obvious—as West remarks on the inevitability of mortality we see a man lift a stark white mannequin from a moving truck through the window of the cab. In another scene, Singer discusses his decision to become a vegetarian as an advertisement on a food delivery truck passes by. In the case of Appiah and Zizek, the location of their interviews—an international airport and a dump—became sets or backdrops that point directly to their remarks and theories. At first I thought these visual puns were a bit contrived but I believe they were conscious decisions by Taylor and are necessary to emphasize the connection between our surroundings and the thought which emerges from our everyday existence.

Judith Butler and Sunaura Taylor discuss the body as they walk through San Francisco’s Mission District in Examined Life

When my professor asked me to consider the gay bar versus the academy she was questioning the site of knowledge production and experience. Of course, I don’t think the answer is one or the other, rather the question itself acknowledges that realizations occur within multiple sites and through a myraid of experiences. Maybe then the issue is how one site is privileged over the other—how what is produced within the academy gains a reputation of prestige and rigor, while what happens at the level of praxis or daily resistance is considered trivial or somehow less evolved. I think it is also an issue of language and I continue to be uncomfortable with the designation of “academic” as it implies that somehow my words carry more weight than someone without the access or even the desire to engage in educational institutions. One of the things I appreciated most about Examined Life is that it makes visual the ways in which the seperation of the academy and that which exists beyond its walls is, in a sense, a falsity. The threads that weave from our personal lives and intimate experiences make their way to into philosophical and theoretical texts, often returning to effect change or at the very least, generate thought and discussion. My hope is that this not forgotten at the level of the academy and even more so, that this reciprocity is acknowledged and cultivated.

Thanks to Eric Kuhn for our conversation that helped jog my memory about the details of the film, Examined Life.

Comments (5)

Thank you so much for your response. It is great to have your voice included and learn more about the specific experiences and political movements that inspired the various texts you mention. It is an inspiration and perhaps a challenge for activists and academics alike, to exist fully within both spheres and more so, to understand and maintain the connections between both areas of our lives.

Well, Butler would say that the experiences come from the street, fearing violence, not knowing to whom to turn, especially if it is from the police that violence comes. Bodies that Matter is all about those non-normative bodies that don’t know if they will be welcome inside the barm so it is about who can enter and who cannot. These are profound experiences of being “abject” or even “unintelligible” within the terms of the everyday. That can be a badge of courage, especially when others wear such badges, but it can also be a scene of fear. Whose bodies finally count? And whose bodies fail to count? When GLBTQ demonstrations amass on the street, as they over these last days, do they get coverage? Are their voices audible? Seems to me that the link with the streets is always there. i was a “street dyke” in the 80s, and i hope it still shows in what i write. if not, i need to work harder. but i’ve tried to take up explicit political questions, especially in Undoing Gender. and i have myself worked as an activist for IGLHRC and others. My early book, Gender Trouble, emerged from bar culture, to be sure, and Undoing Gender emerged more clearly from debates within feminism and increasingly mainstream politics. Bodies that Matter emerged more around the concept of the lesbian phallus, the sense that neither one’s body nor one’s sexuality could be available to language that anyone can understand. i’m much more of an activist on mid east and censorship issues in recent years. but yes, the politics and the theory interweave, but there is always a political issue that drives me to theory – and back again

loved it and I agree there is no right answer.

Hi Julian,

Thank you for the comment. A lot to respond to, indeed.

Yes, I agree that the academy and “the bar,” so to speak, are not mutually exclusive. Like I mentioned, this is what I appreciated about “Examined Life.” The film reminded me of this false divide by making this relationship visual. My frustration with Butler’s text emerged from my own existence within both the world of academia and activism. I don’t think it is an uncommon experience to look to someone like Butler and texts like “Bodies That Matter” for some relevancy within our everyday lives and political struggles. Your point that it is not an activist text is well-taken and I agree. Although I admit that there is and was an initial disappointment in expecting and hoping that Butler could be activated in ways beyond theoretical discussions. Maybe then it is a question of what other texts are discussed in addition to Butler. And this is partly why I appreciate more recent Butler work (I’m thinking of “Precarious Life: The Power Of Mourning and Violence”) because there is a way its accessibility lends itself to activity. Of course there are lessons that I and many others have learned through activism that can’t be replicated in seminar courses and visa versa – multiple sites of knowledge production that are both separate and connected.

I think the interview or more casual conversations in “Examined Life” create points of access for people who might not pick up these texts or who struggle with understanding them. I think this is exciting and does not negate the challenge of reading the texts themselves. Like you said, whatever helps people understand the concepts is important and it seems that “Examined Life” allows for understanding and reinterpretation that moves within and beyond the academy.

Hi Adrienne,

There’s a lot here I’d like to respond to, so I hope you won’t mind if, in the service of conversation, I move rather quickly.

It seems to me that the relationship you draw between “sterile walls of the academy and the communities that exist beyond those walls” is a caricature. First, because of course these two communities are by no means mutually exclusive (there are activists in school and academics “on the ground,” and there are struggles within the school and theoretical self-reflections in those “communities”); and second because the very “limited” or, as you say, “sterile,” quality of the classroom is referring to exactly what makes a seminar structure potentially productive – that is, delimitation of the field of discourse and the number of possible discussants, among other things.

Resistance consumes and develops the theories it needs. Indeed many highly theoretical forms of writing emerge out of political action, and aren’t somehow ancillary to it or separate from it (Many examples here…) Is it possible that the reason Butler in particular hasn’t made it into the activist “street” is not because it is difficult or bad writing (so what if it is – so is Marx difficult and turgid at times), but because it doesn’t put forward, alongside its theories of agency and identity, a real activist project? In fact I recall discussions amongst activists in the 1990s around this exact point; and indeed Nussbaum makes this point in her attack on Butler in 1999 – ad hominem and unkind Nussbaum may have been, but this particular criticism struck a chord for me. Her book is fine as a complex theorization of certain social and political relationships. But deep down Butler’s aren’t activist books.

I haven’t seen “Examined Life.” But isn’t there something to explore or question here about our desire to see theoretical writers humbled and humanized, “difficult” books redeemed by their appealing substitutes (interviews, etc.)? On the one hand, whatever helps you comprehend the ideas is fine; on the other, Butler is relevant in the books (in their very difficulty and form of articulation) or not at all. To think there’s some sublime and potentially activist essence beneath the turgid writing, some secret but hard to access “meaning” separate from the rhetoric, form and conditions of articulation, is to want a different book than Butler’s written.